Ideas for bridging Chinese and English

Notes on tone, structure, and the space between characters

Last updated: Jun 14, 2025

Summary

This text explores ideas for bringing Chinese and English closer through systems, design, and daily communication.

Background

Chinese speakers learning English may find the grammar strange and the words hard to pronounce. English speakers learning Chinese often get stuck on tones, characters, and word order. Even with translation apps or shared vocabulary, real communication can feel incomplete.

And yet, the desire to connect is strong. Students want to learn. Businesses want to work together. Creators want to share ideas. People want to talk.

Ideas

We will explore 7 ideas for language integration, each presented thoughtfully and open-endedly.

1 Introducing English-style spelling conventions to Pinyin

The Problem

Diacritic pinyin (shí / shì) looks foreign to most English readers and is slow to type.

Number pinyin (shi2 / shi4) disrupts eye-flow and feels mathematical.

A good compromise must keep all four lexical tones plus the neutral tone while:

staying on a standard QWERTY keyboard,

avoiding collisions with existing pinyin syllables,

remaining pronounceable for Mandarin speakers,

and looking “English-like” to global users.

Proposal

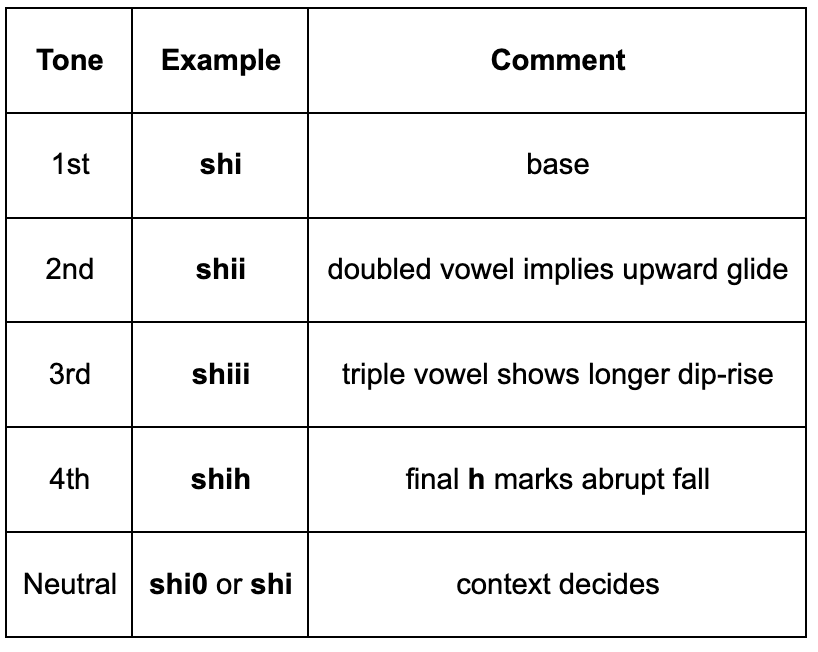

Example solution 1: Tone-Suffix Scheme

Why this set?

r, v, h almost never appear after a Mandarin syllable in Hanyu Pinyin, so collisions are rare

All five forms stay pronounceable for native speakers

English learners see familiar letters, not diacritics or digits mid-word

Suffixes can be stripped by software to recover plain pinyin if needed

Example solution 2: Vowel-Length Scheme

Pros: visually intuitive once learned, no new alphabetic symbols.

Cons: variable string length complicates search / tokenization; easy to mistype.

Why It Helps

Makes tones easier to learn by mimicking familiar English spelling. Reduces the need for diacritics or numbers, easing global use in chat, subtitles, and apps.

2 Vocabulary Expansion & Loanwords

The Problem

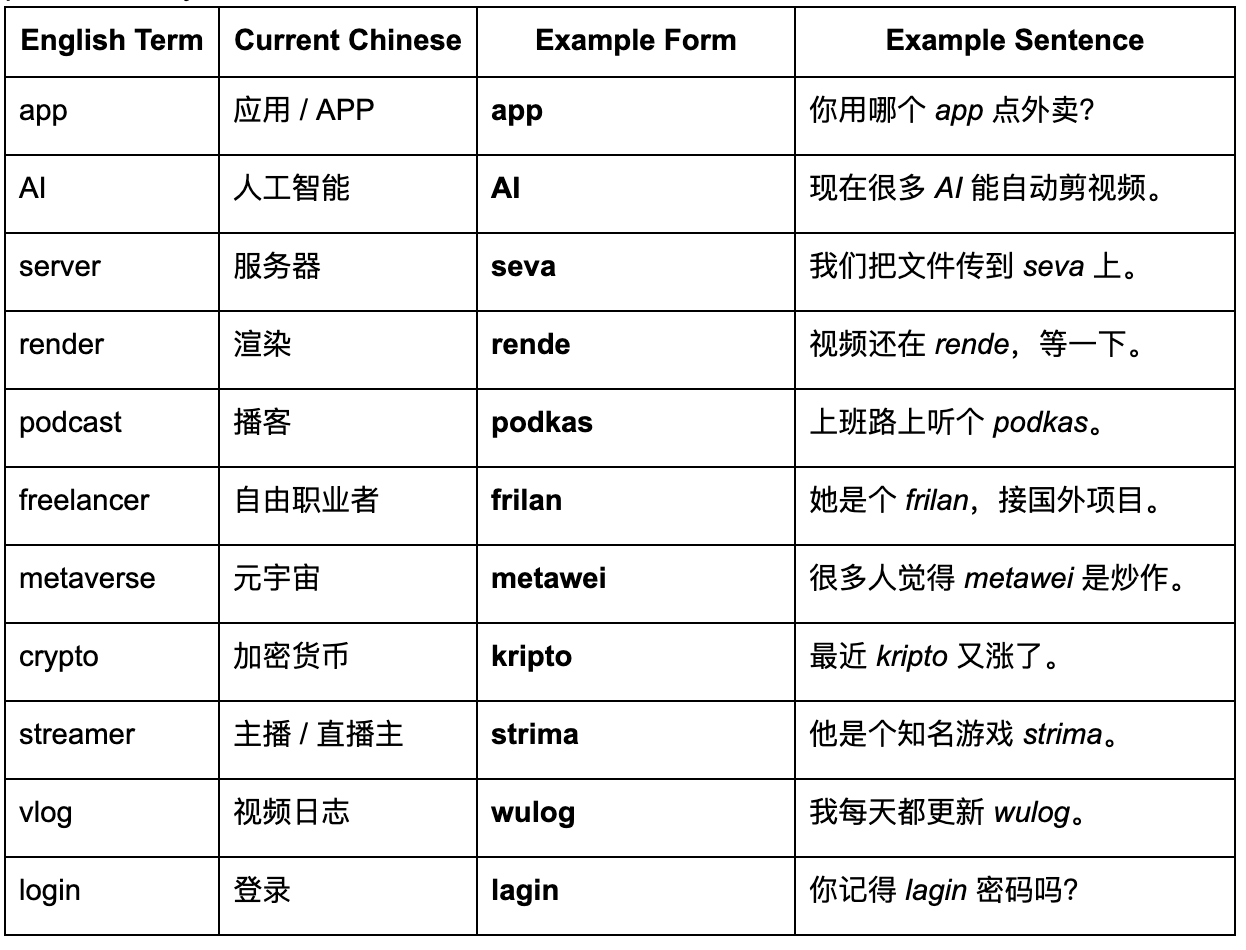

Mandarin speakers use more global tools, media, and platforms than ever. But when it comes to modern English words, Chinese often relies on long, unclear translations or inconsistent phonetizations. This slows communication and hides the English origin from learners.

Proposal

Use standard English spelling for short, widely known terms.

Use simplified romanized forms (Pinyin-friendly) for longer or awkward words making them easier to pronounce, type, and recognize.

Example Vocabulary

Why It Helps

Introduces global terms naturally, reducing awkward translations and shortening expressions. Builds comfort with English vocabulary while keeping speech fluent and familiar.

3 Hybridized Grammar

The Problem

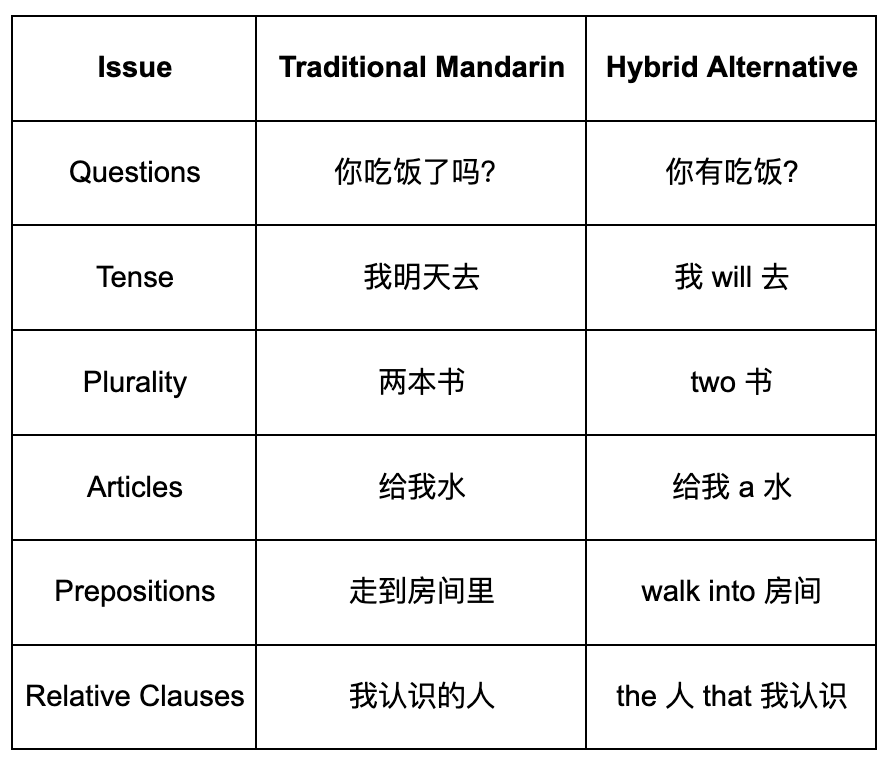

Mandarin and English express meaning through different systems: particles and context vs. fixed structure and auxiliary verbs. Learners switching between them face constant friction.

Proposal

Gently align Mandarin syntax toward familiar English grammar patterns, tense markers, article hints, simplified prepositions, while keeping core vocabulary and flow intact.

Grammar Tweaks by Category

Why It Helps

These soft adjustments reduce mental rewiring for learners and make bilingual communication feel more natural, especially in subtitles, casual speech, and online writing.

4 Contextual Semantic Disambiguation in Pinyin

The Problem

Pinyin is compact but overloaded. Most syllables each map to dozens of characters. Meaning depends entirely on context, making reading and learning difficult without hanzi.

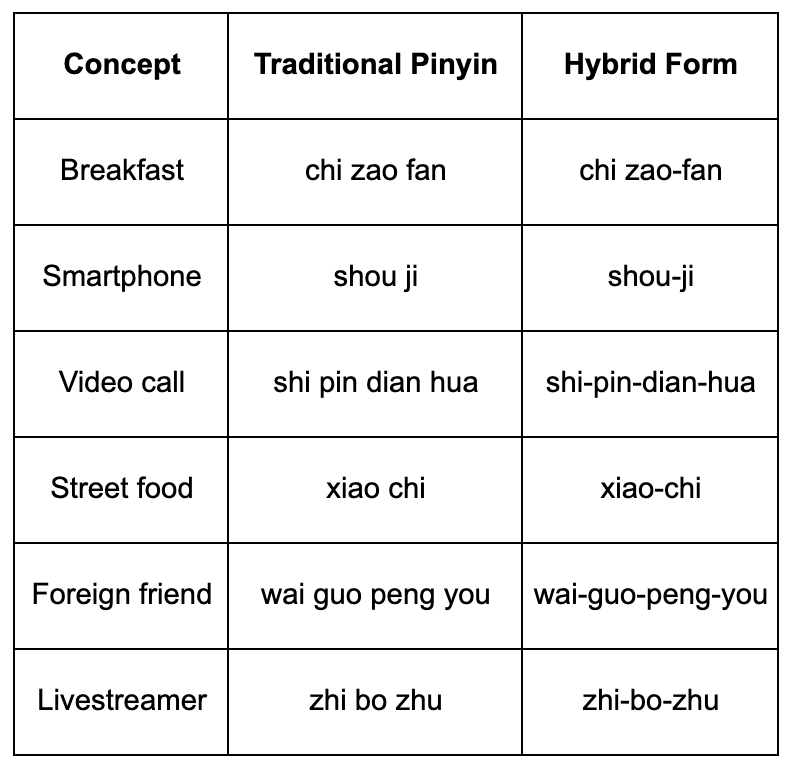

Proposal

Introduce light structural markers—such as hyphens—to segment multi-syllable compound words in Pinyin. This makes meaning boundaries clearer without relying on hanzi.

Why It Helps

Adds minimal structure to make Pinyin more readable, teachable, and searchable—especially for beginners and bilingual users.

5 Adaptive IMEs & Predictive Clarification

The Problem

Pinyin is highly ambiguous. A single syllable like shi can map to dozens of words (是, 市, 师, 诗, 食…). Hanzi disambiguates meaning, but forces learners to rely on a separate symbolic system. Standard IMEs resolve this silently, hiding the choice logic.

Proposal

Make disambiguation visible, contextual, and user-facing. Instead of instantly replacing input with hanzi, the IME offers meaning-first suggestions—showing semantic tags, icons, and context pairings before character selection. This teaches by doing.

Example Single-Syllable Disambiguation

User types: shi

Candidate bar shows:

Why It Helps

Clarifies meaning at the point of input, reducing reliance on character memorization. Helps users learn through context and repetition, while making Pinyin more expressive and usable in daily communication.

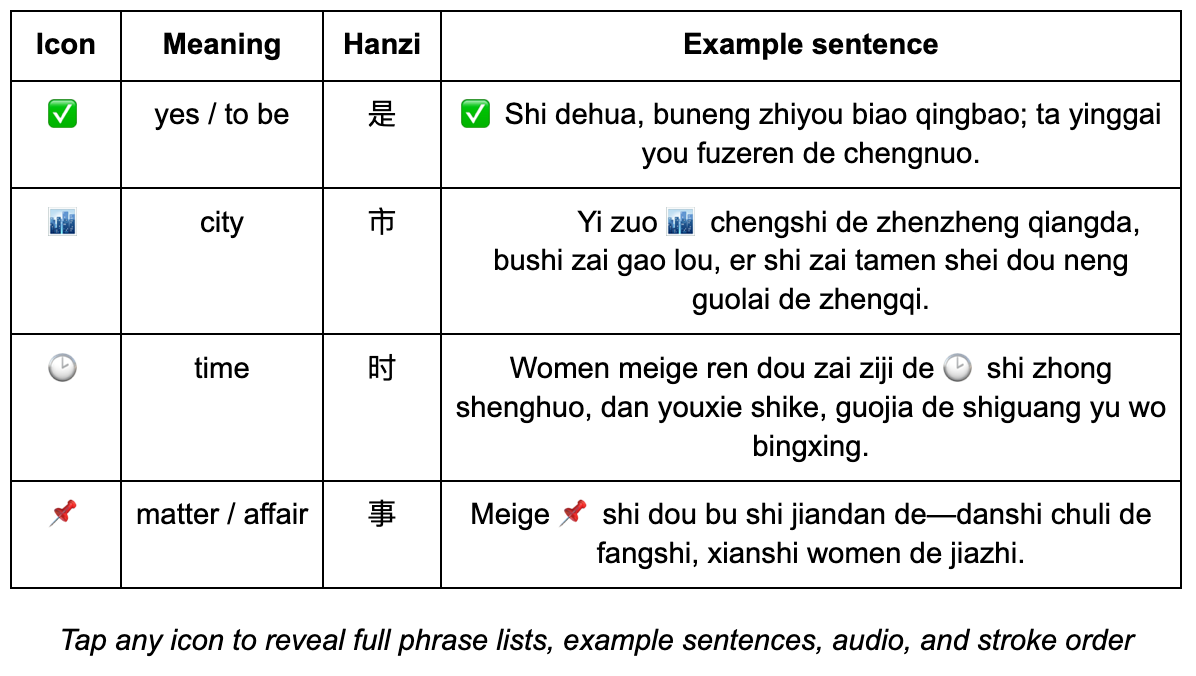

6 Digital Pinyin Dictionary with Semantic Icons

The Problem

Standard dictionaries rely heavily on hanzi and assume a certain level of literacy. For beginners and cross-language users, it’s difficult to go from sound to meaning without knowing characters.

Proposal

Build a visual-first online dictionary organized by Pinyin syllables. Each entry shows icons or emoji representing core meanings, with English and hanzi as optional layers. Users search by sound; tones and semantic icons guide understanding. Tapping reveals full definitions, usage, audio, and writing guides.

Sample Entries

shu

shi

Why It Helps

Makes Pinyin self-sufficient and intuitive for learners. Lowers the barrier to meaning recognition, supports multilingual use, and reinforces language through visual memory.

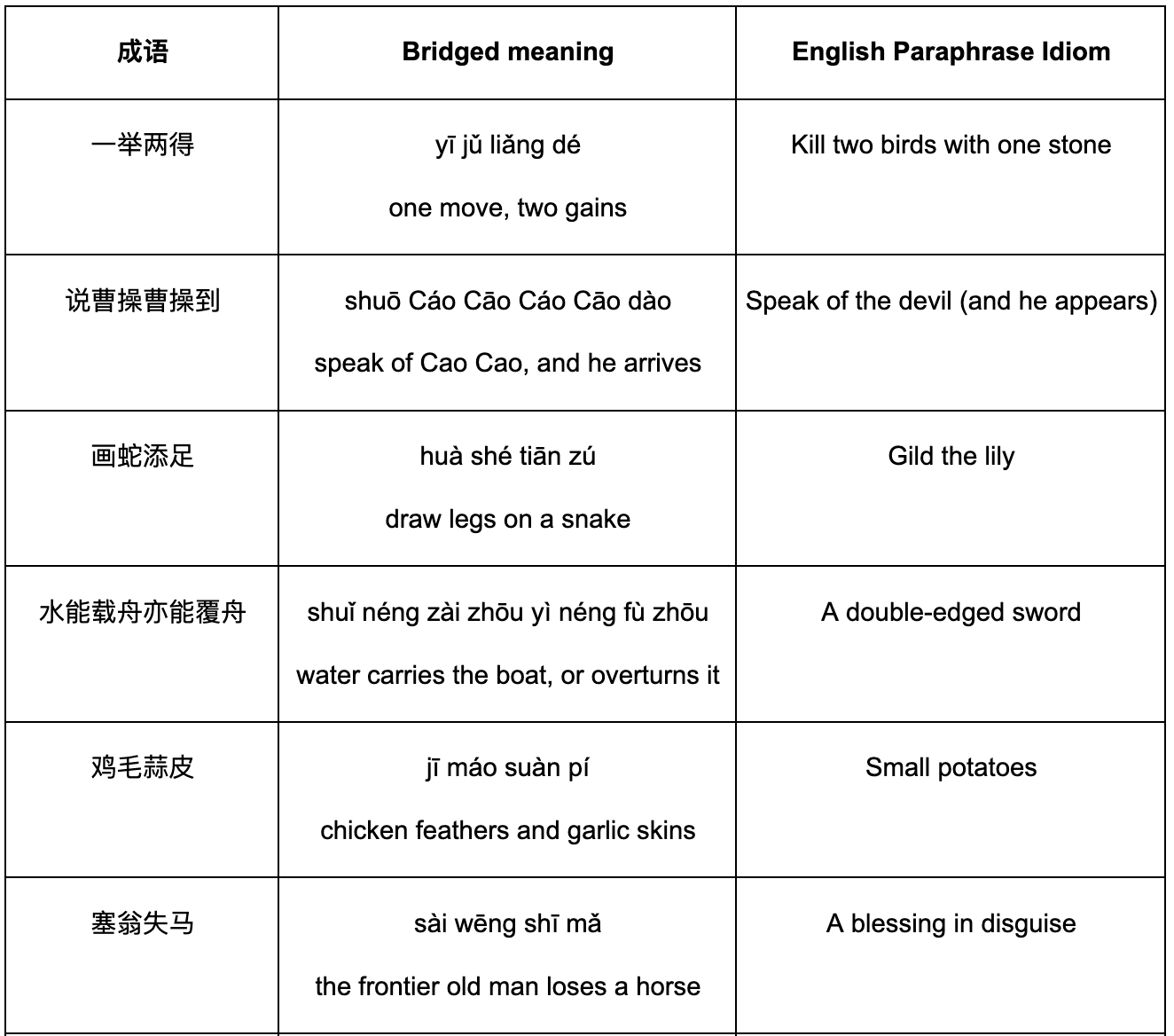

7 Cross-Language Idiomatic Pairing

The Problem

Idioms are rich in meaning but often untranslatable. Learners struggle to grasp or use them across languages without losing nuance or sounding unnatural.

Proposal

Pair high-frequency Chinese chéngyǔ with familiar English idioms in subtitles, keyboards, learning apps, and media. Display both together to reinforce equivalence and promote code-switching comfort.

Why It Helps

Preserves cultural depth while building intuitive bridges between expressions. Makes idioms easier to learn, recall, and apply in bilingual settings. Signals cultural fluency across communities.