Done Is Gold

Inside the psychology of perfectionism and a practical playbook for shipping

Perfectionism Is Fear Disguised as Virtue

If you’d asked me a decade ago what my “biggest weakness” was, I would have responded proudly: perfectionism. I wore it like a badge of honour — a sign that I cared deeply about my craft.

But what if that badge isn’t a virtue at all? What if it’s a mask for fear — fear of judgment, failure and losing control — and it’s costing us our best work?

Every app we admire shipped messy first versions.

Slack started life as a humble chat tool spun out of a failed gaming company. Figma iterated for years in beta. Even Apple’s first iPhone had glaring flaws.

Yet many solopreneurs and small‑team founders still tinker in private, convinced that one more tweak will make their product irresistible. Speed to market decides winners, and this obsession with flawless launches doesn’t just waste energy — it erodes momentum and burns out talented creators.

Perfectionism is seductive because it whispers, “You’re being responsible.” In reality, it’s fear wearing a polished mask. The internal resistance we feel when we sit down to write a newsletter or hit publish is born of anxiety, not excellence. Steven Pressfield, author of The War of Art, calls this sabotaging force “Resistance.” He notes that resistance is experienced as fear and that “the degree of fear equates to the strength of Resistance”. When we care deeply about a project, fear rushes in, convincing us to wait until everything is perfect.

Truth: what feels virtuous is often avoidance.

The Perfectionist Paradox: Strength or Fear?

You’ve heard the job‑interview cliché: “My biggest flaw? I’m a perfectionist.” It resonates because it flatters our self‑image. High achievers equate high standards with virtue. Yet psychologists distinguish between healthy striving and maladaptive perfectionism. Harvard’s Jessica Kent explains that self‑oriented perfectionism involves unrealistic expectations for oneself, other‑oriented perfectionism involves unrealistic expectations for others, and socially‑prescribed perfectionism involves believing that others expect perfection from you. Healthy striving focuses on excellence within realistic limits; perfectionism demands flawless results and punishes anything less.

Pressfield’s concept of resistance helps clarify why we cling to perfectionism. In his essays, he notes that artists and warriors live by one primal emotion — fear. Fear stops us from beginning our work, from carrying it forward in the face of adversity and from finishing it when we’re close to completion. Fear of success, fear of failure, fear of exposure and fear of venturing from the known to the unknown all masquerade as high standards, but they stem from vulnerability. When we call ourselves perfectionists, we signal diligence, but subconsciously we’re shielding ourselves from criticism.

“Perfection is the enemy of progress.” — Winston Churchill

A recent Forbes piece observes that waiting for perfection is a mask for fear that prevents growth. The author lists behaviours like over‑planning, avoiding accountability and clinging to sunk costs as manifestations of fear of failure. When we over‑edit for weeks instead of launching a minimum viable product, we’re not being strategic — we’re self‑sabotaging.

How Perfectionism Sabotages Digital Builders

Perfectionism feels like quality control, yet it is intimately tied to procrastination, imposter syndrome and burnout. An Intelligent Change article points out that perfectionism is followed by shadows like procrastination, writer’s block, overthinking, lack of motivation and burnout. The darkest shades are resistance and fear. Pressfield’s Resistance rationalizes your excuses, projects self‑doubt into your routine and can paralyze you from reaching your goals. It feasts on fears — fear of not being good enough, fear of failure, negative feedback or being selfish. This internal saboteur keeps you on a hamster wheel of over‑preparation.

The costs aren’t just lost time. Harvard notes that perfectionism is on the rise among young people and correlates with lower self‑esteem, anxiety and depression. Social media amplifies these pressures: the Dove Self‑Esteem Project found that by age 13, 80 % of girls distort the way they look online, and these distortions are linked to anxiety and depression. When our feeds are full of curated success stories, it’s easy to internalize unrealistic standards and feel “behind” in life.

For entrepreneurs, the stakes are higher. Forbes warns that fear of failure manifests as perfectionism, over‑planning and avoiding accountability. Fear keeps entrepreneurs from investing in new products or seeking feedback, leading to stagnation. The article notes that fear is a survival instinct rooted in biology: our brains prioritize safety over growth, and when we equate our worth with our success, failure feels catastrophic. For creative founders, overworking to meet impossible standards leads straight to exhaustion. Boston University’s Questrom School of Business notes that burnout often travels alongside perfectionism, with early signs including feeling overwhelmed by basic tasks, irritability, procrastination and seeing vacation solely as recovery time. When we obsess over polish, we sacrifice momentum and well‑being.

Roots of Fear: Where Unrealistic Standards Come From

Perfectionism doesn’t spring from nowhere. It often begins in childhood and is reinforced by social conditioning. Startups Magazine highlights that our survival instincts begin in childhood; a child who was criticised for mistakes or taught that visibility was unsafe may struggle with risk and self‑expression later on. Such individuals learn to equate being seen with danger. A founder praised for being “the smart one” might feel immense pressure to never make mistakes, leading to procrastination, burnout or avoidance of new challenges.

Harvard’s research into perfectionism identifies three forces that drive it: self‑imposed standards, expectations from others and socially prescribed pressures. Studies show that levels of perfectionism in college students increased significantly between 1989 and 2016, with societal pressure increasing at twice the rate. Many perfectionists were historically rewarded for being “the good student” or “the responsible kid” and internalize the belief that mistakes equal rejection. A 2022 study of 16‑ to 25‑year‑olds found that 85.4 % identified perfectionist traits focused on academic achievement and experienced stress impacting their physical and mental health.

Social media magnifies these pressures. Intelligent Change notes that by age 13, most girls already feel compelled to edit their appearance online, leading to anxiety and depression. Our feeds show curated highlight reels, not messy drafts. It’s easy to forget that every entrepreneur’s overnight success was years in the making.

Reminder: the stories you admire had messy beginnings.

The Science Behind Progress: Growth Mindset and Imperfection

So what’s the alternative? Research on growth mindset offers an answer. Educational psychology shows that abilities can develop through effort and feedback leads to higher achievement and resilience. A progress‑orientation acknowledges that each mistake is a valuable lesson and encourages risk‑taking and experimentation. In technology and creative industries, this mindset fuels innovation. The Cosmico article notes that the iterative process of software development—exemplified by agile methodology—prioritizes rapid prototypes and continuous improvement, allowing companies to adapt quickly and stay ahead in fast‑moving markets.

Perfectionism, by contrast, is a formidable barrier to creativity. It creates “creativity paralysis,” where fear of criticism or failure stifles the free flow of ideas. When we demand flawless results from the outset, we hesitate to practice openly, explore new techniques or experiment. This environment punishes trial and error — the very process through which mastery emerges. The article highlights how progress encourages learning and adaptability, whereas perfectionism leaves little room for the mistakes that lead to breakthroughs.

Perfectionism also takes a toll on mental health. The relentless pursuit of flawlessness breeds chronic stress and burnout, trapping people in anxiety and inadequacy. Embracing imperfection through realistic goals, self‑compassion and celebrating small successes improves well‑being and offers relief.

As a recovering perfectionist, I’ve experienced this shift firsthand. When I embraced the idea that my first draft doesn’t have to be my final draft, I felt freer to experiment. Imperfect action built confidence. Each messy newsletter taught me more about my audience than hours of private tinkering ever did.

Shift From Polish to Progress: Practical Strategies

Overcoming perfectionism isn’t about lowering your standards. It’s about shifting your mindset from fear of failure to growth and learning. The evidence‑backed strategies below will help you move from polish to progress:

Set a “good enough” threshold: Instead of chasing flawless output, set a threshold for each project. Tess Browne recommends breaking big goals into bite‑sized tasks and celebrating small wins rather than waiting for a final perfect result. Harvard’s Questrom School urges us to replace avoidance goals (“don’t mess up”) with approach goals (“showcase what I’ve learned”), which keeps us moving forward.

Reframe failure as feedback: Reframing failure as data helps us see each iteration as learning instead of proof of inadequacy. Startups Magazine reminds founders to launch before it feels perfect and to treat setbacks as lessons.

Challenge your inner critic: Progress also requires kindness toward yourself. Swap thoughts like “This isn’t good enough” for “This is a draft, and I can improve it.” Freedom Mastery suggests speaking to your fear with compassion and time‑boxing your loop — allocate a fixed window to draft or design, then publish.

Start before you feel ready: Begin before you think you’re ready, connect to the “why” behind your work and track momentum rather than outcomes. Each shipped version builds courage and attracts collaborators.

Tools and Frameworks for Iterative Creation

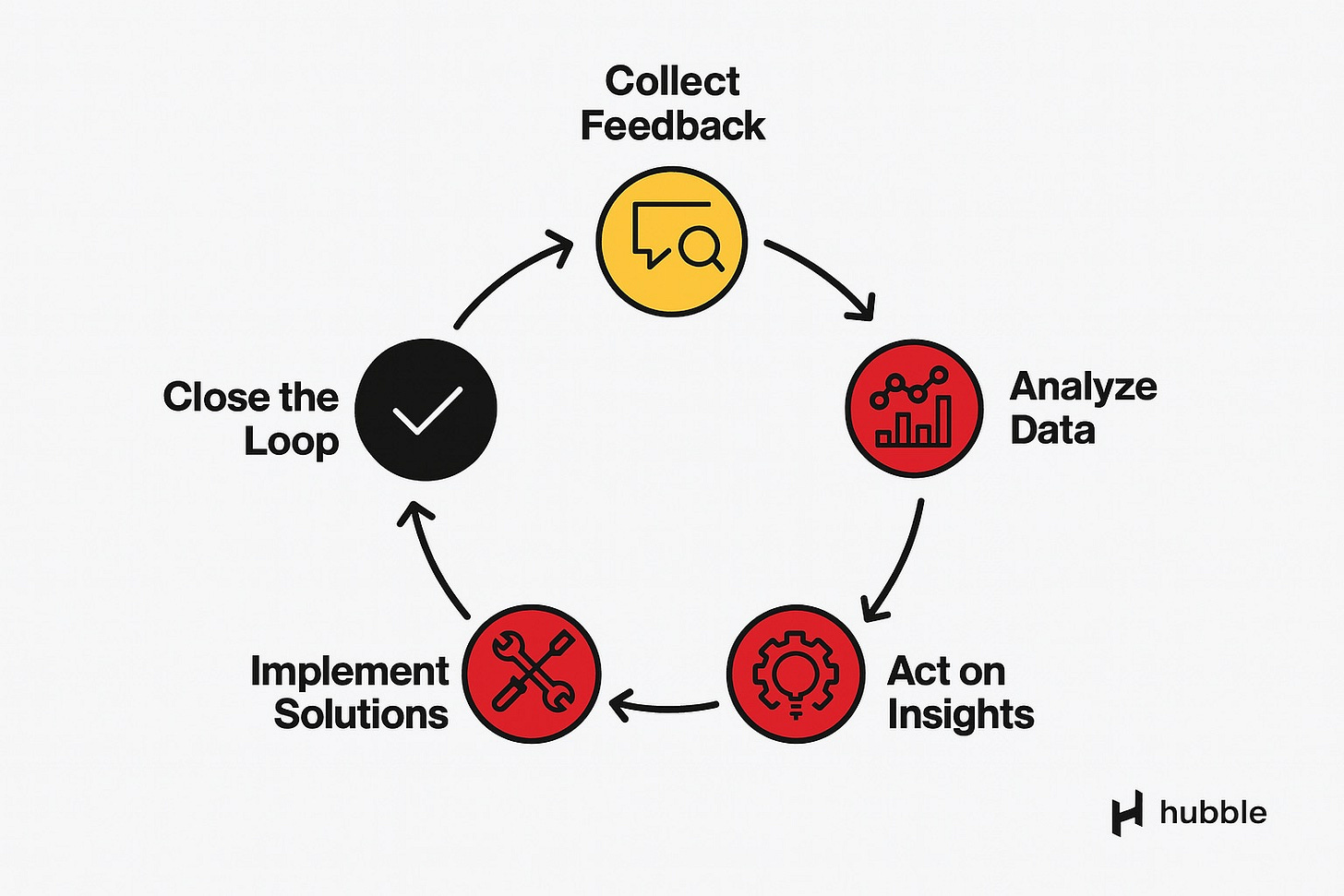

Adopting a progress mindset isn’t just psychological; it’s operational. Digital builders can borrow from the playbooks of product teams by using minimum viable products (MVPs), agile sprints and rapid experimentation. The tech industry shows how iterative cycles accelerate learning. Cosmico notes that the iterative process of software development — exemplified by agile methodology — prioritizes rapid prototypes and continuous improvement. Launching early versions, gathering feedback and iterating allow you to adapt quickly and stay relevant.

Think like a product manager: ship, test, iterate.

Start with an MVP that solves the core problem for a small group of users. Use A/B tests to compare hypotheses and let the data guide your decisions. Co‑create with your audience: build in public, share drafts and invite user feedback. Time‑box experimentation: allocate a few days to develop a new feature and release it to testers. Schedule regular reflection sessions focused on momentum, not just outcomes. Ask: What did we ship this week? What did we learn? What will we try next?

These frameworks can apply to content creation, coaching offers or digital products. For example, instead of spending months crafting a perfect online course, create a live beta cohort. Deliver modules in real time, gather feedback and refine your curriculum. The process generates revenue and insights simultaneously. The first version will be imperfect by design — but that’s the point.

Case Studies: Launching Imperfectly and Winning

Many successful companies are built on messy first drafts. Instagram started as Burbn, a location‑based check‑in app that pivoted after users gravitated to its photo‑sharing feature. Airbnb’s founders launched with a simple website to rent out air mattresses in their apartment; the first photos were taken with a phone camera. These early versions were far from polished, but they validated demand and attracted feedback that shaped the eventual product. Slack’s origin story began with a failed game; the team repurposed their internal chat tool and released a minimal version, refining it based on user feedback. The ability to iterate quickly — rather than waiting for perfection — allowed these companies to capture momentum and adapt to user needs.

These stories reinforce the principle that momentum attracts attention. Investors and customers are drawn to projects in motion, not to polished plans sitting in drafts. As one Forbes author notes, fear of failure leads entrepreneurs to overplan and avoid risk, whereas those who launch early and iterate reap the benefits of adaptive learning. Being seen — warts and all — builds trust. When you share your process, you invite collaboration and demonstrate resilience.

Embrace Imperfection as a Superpower

Perfectionism isn’t a noble trait; it’s a fear‑based pattern that robs creators of momentum and joy. It masquerades as high standards while feeding on our deepest anxieties. Evidence from psychology shows that perfectionism is linked to procrastination, burnout, anxiety and depression. By contrast, a progress mindset rooted in growth, experimentation and self‑compassion leads to learning, creativity and well‑being.

As entrepreneurs, we don’t have the luxury of hiding behind drafts. In a climate where speed to market determines winners, obsessing over polish is a liability. The good news is that imperfection is not just acceptable — it’s a superpower. Every rough draft contains the seeds of a masterpiece. Every beta test is a chance to learn. When we redefine success as consistent improvement and courageous action, we free ourselves to build businesses that evolve with us.

So here’s your invitation: pick one project you’ve been polishing for too long. Set a timer, finish the next step and share it with a real person. Ask for feedback at 80 % complete. Celebrate the launch, however small. Write down what you learned. Then do it again tomorrow. Progress compounds like interest. Perfectionism keeps your best work trapped in your head; progress releases it into the world.

--

If this resonated, consider subscribing or sharing it with someone who needs to hear it. More reflections, experiments, and imperfect drafts coming soon.

— Brian